In the summer of 1937, with the Dodgers holding down their familiar spot near the bottom of the National League, the cartoonist Willard Mullin drew the unforgettable image of the “Brooklyn Bum” — a potbellied, cigar-chomping hobo who combined the cheerful ineptitude of the players and the goofy optimism of their fans. Named for the singular “dodging” skills of pedestrians in a borough crammed with trolley lines, the Dodgers hadn’t captured a pennant since 1920, and had never won a World Series. “Brooklyn?” roared Bill Terry, manager of the hated New York Giants. “Is Brooklyn still in the league?” Dodger fans were largely immune to this abuse. Their addiction had taught them patience and humility — like belonging to a religion whose one flaw was an unreachable promised land. From Bay Ridge to Brownsville, from Flatbush to Coney Island, it was always “Wait till next year.”

Their shrine was Ebbets Field, a crumbling edifice known for its obstructed views and peculiar dimensions. Stretching across right field, a mere 297 feet to the foul pole, was a hand-operated scoreboard with a wire screen above and a wall of advertisements below, the oddest one daring the batter to “Hit Sign, Win Suit” from Abe Stark’s haberdashery. Bleacher cheers were led by the bell-clanging Hilda Chester, whose signature taunt — “Eacha heart out, ya bum” — easily reached both dugouts. Baseball’s premier organist, Gladys Gooding, performed between innings, while the oddball “Dodgers Sym-Phony” entertained in the aisles. Players were introduced by the grammatically challenged Tex Rickards, who reminded customers, “Don’t throw nuthin’ from the stands!” Once, spotting some coats hanging over the bleacher wall, Rickards announced, “Will the fans along the railing in left field please remove their clothes.”

The Dodgers did win the pennant in 1941. But normal life returned a week later when Mickey Owen, their all-star catcher, muffed a third strike with two outs in the ninth inning of Game 4 against the Yankees, costing Brooklyn the victory and, many believed, the team’s first World Series. It was yet another of those special Dodger moments: something to pass down to innocent children but, ultimately, to forgive. Why blame the catcher when a higher power was at work? (Sixty-four years later, when Owen took his final third strike, the obituary in The New York Times carried the headline “Mickey Owen Dies at 89; Allowed Fateful Passed Ball.”)

Hopes rose again in 1942 with the news that Branch Rickey, the former general manager of the St. Louis Cardinals, had taken a similar post with the Dodgers. Rickey’s teams had won four World Series, the last one coming against the Yankees that same year. He had left the Cardinals in a dispute over money; what awaited him in Brooklyn seemed far less appealing. But Rickey had a plan to revolutionize the game, and St. Louis, a segregated city, offered no hope for its success.

Much has been written about his role in the integration of major league baseball, and Jimmy Breslin’s slim biography, “Branch Rickey,” breaks no new factual ground. What Breslin has done, with his usual gritty perception, is revive a story of enormous consequence. Branch Rickey (1881-1965), a white man, is rarely mentioned when the great civil rights leaders are discussed. His politics were small-town Republican, his judgments often puritanical. He had numerous reasons for integrating baseball, Breslin reminds us, not all of them noble. But without his vision and persistence, civil rights may have taken an even slower, rougher path.

According to Rickey, his first whiff of prejudice came in 1904, during his time as a student-coach at Ohio Wesleyan University, when a black ballplayer was denied access to a hotel. Enraged, Rickey took the player to his room, ordered up a cot and made it clear that the team stayed together or left together. (They stayed.) Rickey hoped to play major league baseball. A mediocre prospect, he spent time with the St. Louis Browns and the New York Highlanders (renamed the Yankees in 1913) before injuries ended his career. Obtaining a law degree, he returned to baseball as manager of the Browns before switching leagues to run the crosstown Cardinals in 1917.

Above all, Breslin insists, Rickey was a businessman, and his genius lay in developing the best talent for the least money. He invented the farm system, which “gathered players of promise and grew them, like crops, on minor league teams. . . . The practice was modeled somewhat after the Southern system of slavery.” Farm clubs not only helped the Cardinals, they also made Rickey a rich man. With so much talent on hand, he sold players to other organizations at a personal commission of 10 percent. And his contract talks — a lawyer jousting with the barely educated — were painfully one-sided. Dizzy Dean, the league’s best pitcher, recalled going to see Rickey about a small loan. “He didn’t give me any money,” Dean confessed. “All I got was a lecture on s*x.”

In Brooklyn, Rickey shifted gears. The team needed better players, which its farm system was unable to provide. So he looked elsewhere, to the Negro leagues, where talent abounded. His first task was to find the right man to break the color line. “I don’t know who he is, or where he is,” Rickey told Red Barber, the Dodgers’ radio announcer, “but he is coming.”

The story is familiar. Breslin, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, is a master of the spare narrative. His strength lies in the telling, not in the research. Until Rickey came to Brooklyn, he writes, “baseball was a sport for hillbillies with great eyesight.” While Jackie Robinson wasn’t the best player in the Negro leagues, his background clearly set him apart. A four-sport athlete at U.C.L.A., he was well educated, soon to be married and quite comfortable playing on integrated teams. His main problem was his temper. As an Army lieutenant during World War II, he’d been accused of threatening a white driver who used a racial epithet while demanding he move to the back of a bus. At their legendary meeting in Brooklyn in 1945, Rickey, knowing full well what lay ahead for the first black major leaguer, peppered Robinson with racial slurs. “Mr. Rickey, do you want a ballplayer who is afraid to fight back?” Robinson asked. No, came the reply. “I want a ballplayer with guts enough not to fight back.” Robinson relented; Rickey found his pioneer.

Dodger fortunes changed almost overnight. Brooklyn, a borough of immigrant enclaves, welcomed Robinson as one of its own. And he responded to racial taunts on the road with truly spectacular play, winning rookie of the year honors in 1947. The Dodgers would soon come to dominate the National League, though Rickey would not be there to share the glory. Forced out in 1950 in another dispute over money, he moved on to the lowly Pittsburgh Pirates, creating the nucleus of yet another championship team. But his heart remained in Brooklyn, Breslin says, and his best work did, too. By the time the Dodgers won their first World Series, in 1955, there were four black players in the starting lineup — five when Don Newcombe took the mound. For Dodger fans, the long wait was over. “Next year” had finally arrived.

Had Rickey not chosen Jackie Robinson, he might have turned to Roy Campa¬nella, the rifle-armed, power-hitting Negro league catcher who joined the Dodgers a year later, in 1948. Campanella was an extraordinary talent; he would win the Most Valuable Player award three times, and be voted into the Hall of Fame. What kept him from going first, Neil Lanctot says in “Campy: The Two Lives of Roy Campa¬nella,” a faithful if overstuffed biography, were the deficiencies common to most players of his era, black and white alike. Campy was a high school dropout. He loved the temptations of the road, despite having a wife and children at home. And there was something else: Campy, born to an African-American mother and an Italian-American father, may have been too fair-skinned for Rickey, who wanted no confusion surrounding the black man who would break the color line.

Campanella led two distinct lives, as the book’s subtitle suggests. The first one, as a baseball star, ended when he apparently fell asleep at the wheel of his car in 1958. The second one, as a quadriplegic, ended with his death in 1993 at the age of 71. Lanctot, a baseball historian, says that what these lives had in common was an absence of bravado and complaint. Campy was no crusader. He led quietly, by example, and he rarely rocked the boat.

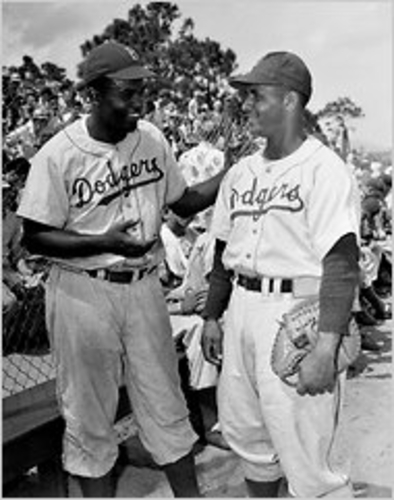

The Dodgers of the 1950s were a team of stars: Robinson and Campa¬nella, Duke Snider and Carl Furillo, Gil Hodges and Pee Wee Reese. The clubhouse was cohesive, but the players socialized by race. Robinson and Campy became fast friends, rooming on the road, taking jobs together in the off-season and buying their first homes in the same neighborhood in Queens. Perhaps the best parts of “Campy” chart the breaking of their bond. Campanella’s son described his father as “the quintessential jock” who lived to play the game. Robinson, for his part, saw baseball as a means to larger ends. He pushed his reluctant black teammates to speak out against racism and to protest their exclusion from restaurants and hotels. Campy refused. “I’m a colored man,” he told a reporter. “A few years ago there were many more things I couldn’t do than I can today. I’m willing to wait.”

When Robinson retired after the 1956 season, the two men were barely speaking. Even Campa-nella’s car accident failed to end the feud. In 1963, Robinson invited black players to share their experiences for a book he was writing on civil rights and baseball. To his delight, Campy spoke passionately about what he had gone through and what needed to be done. “I am a Negro and I am part of this,” he said. “I feel it as deep as anyone, and so do my children.”

The two reconciled — one now in a wheelchair, the other ravaged by diabetes and heart disease. At Robinson’s funeral in 1972, Campy sat near the coffin, humming softly. He was at peace. The bond had been restored.

David Oshinsky, a frequent contributor to the Book Review, teaches history at the University of Texas and New York University.

Posted By: Richard Kigel

Posted By: Richard Kigel

Saturday, March 26th 2011 at 10:33AM

You can also

click

here to view all posts by this author...