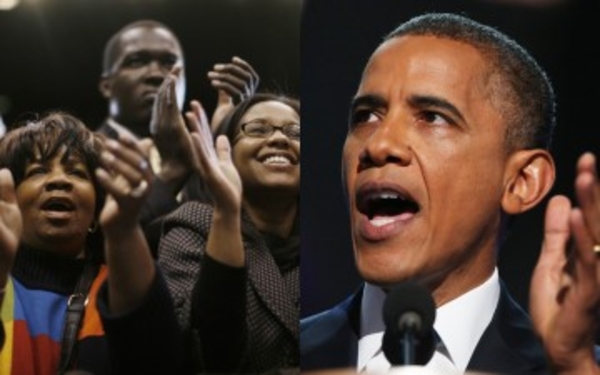

More than 50 years after the publication of Ralph Ellison's "Invisible Man," black men appear more visible than ever -- a freshman senator from Illinois, Barack Obama, is the American Idol of national politics, and Will Smith is perhaps the most bankable star in Hollywood. Yet black men who put their kids through college by mopping floors, who sit at home reading Tennyson at night, who wear dreadlocks but design spacecraft, say it sometimes seems as if the world doesn't believe they exist.

The dueling realities of their history -- steady progress and devastating setbacks -- continue to burden many black men in ways that are sometimes difficult to explain.

"As a black man, you often think that things can go either way," says Todd Boyd, an African American who has carved out a niche exploring race and popular culture as a professor at the University of Southern California. "You could be that guy in the penitentiary, or you could be that guy on everybody's television screen."

You could be Gilbert Arenas, an NBA all-star who makes millions of dollars a year but still feels he relates to the "young brother" who catches the bus every day to fry burgers for a living. "We have an unspoken bond about life," he says.

The statistics that spell out the status of black men are often conflicting, sometimes perplexing.

The percentage of black men graduating from college has nearly quadrupled since the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, and yet more black men earn their high school equivalency diplomas in prison each year than graduate from college. Black families where men are in the home earn median incomes that approach those of white families. Yet more than half of the nation's 5.6 million black boys live in fatherless households, 40 percent of which are impoverished. The ranks of professional black men have exploded over four decades -- there were 78,000 black male engineers in 2004, a 33 percent increase in 10 years. And yet 840,000 black men are incarcerated, and the chances of a black boy serving time has nearly tripled in three decades, Justice Department projections show.

So where does that leave 17-year-old Jonathan McMaster as he ponders his future? The statistics show that fewer than half of black boys graduate from high school four years after entering the ninth grade. And yet here he is, a junior at Baltimore's exclusive Gilman School, running track, playing the viola in the school orchestra, approaching fluency in French. He has visited nearly 30 countries and is spending a month studying in London. It used to be "a hindrance" to be a black man, McMaster says he's been told by his elders. "But with everybody trying to diversify now, I think it has become almost an advantage."Where the nation was once largely segregated along a black-white divide, the country has become more racially and ethnically mixed, creating opportunities -- !

Posted By: DAVID JOHNSON

Posted By: DAVID JOHNSON

Thursday, December 20th 2012 at 10:16AM

You can also

click

here to view all posts by this author...