It was the middle of the night. Something woke me out of a deep sleep. It was so dark my eyes were useless. But I could still hear. Somebody was moving. There was a gentle sound of bare feet tapping on the dirt floor.

I was half asleep but in the darkness I could make out a dim figure heading for the door. By his shape I saw that it was Ol' Mose sneaking out into the night.

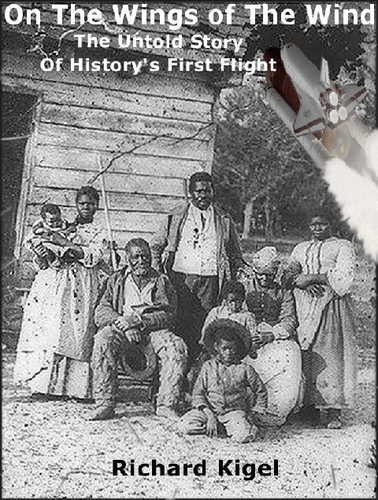

By the sound of their breathing and snores, I could tell the others were just where they were supposed to be, eight of us, snugly tucked away in our little wood cabin, with just enough room to roll over.

Everyone had a place on the floor. Our beds were nothing but boards covered with straw. At least we didn’t have to feel the cold earth knifing through our bones. We didn’t mind the hard beds so much. Time to sleep was far more important.

Sleep transported us to a far away place, away from the troubles of this life. Sleep was where we found our only rest. It was the only place we could be left alone and undisturbed. So I closed my eyes and soon I didn’t know anything about this hard cruel world.

And I stayed not knowing and happy about it until that infernal horn blasted into my dreams. Only I wasn’t dreaming. It was real. The horn meant our peace was done and we had to get ready for work.

I looked around in the dark, trying to see into the corner where Ol’ Mose stays. I expected to see an empty bed. I thought maybe he ran off. But he was there, flat on his back, stretching, yawning and groaning his way into the waking world like everyone else.

Auntie Bee was already bending over the fire, cooking up some hoe cakes. This was our usual breakfast and I will say this—you could do a lot worse. Hoe cakes were nothing but corn meal and water or buttermilk if we had any. She’d pat some flour dough into bite size cakes and lay them on the flat end of a hoe like one we might use in the field. Then she’d bake them in the fire. When they were done, she would pull them out, rub off the ashes and run them under warm water.

Those hoe cakes were just fine. When you got them straight off the fire, man, were they ever good.

Auntie Bee took care of us here in the cabin. By the time we’d stagger to our feet she’d already been up a good long while. Every morning you would see her beginning her chores here in the cabin—and all before she left to work for the Missus at the Big House.

Before anyone was up, Auntie Bee would start the fire and boil water to cook our lunch. She would prepare baskets for all of us and gourds filled with food and water so we had something to eat in the field that day.

Auntie Bee was the one who kept our cabin decent. Every morning, before the sun, she’d sweep the dirt floor with a straw broom so we wouldn’t step on any rocks or twigs or spiders. When Auntie Bee told you something you had better listen if you knew what was good for you. That broom of hers made a powerful switch. If you didn’t watch yourself, you’d be liable to feel the shock of that hickory handle upside your head.

Once a week, Massa gave us bacon from the smokehouse. Often it was filled with worms so Auntie Bee had to throw out a good amount. Still, she would find enough to make salt pork. She cooked rabbit and possum the men caught in the woods. We had oysters, crabs and herring from the river. Fish were plentiful. We lived off fish.

We always had vegetables from our own gardens. There was a patch of ground behind the slave quarters where we grew corn, cabbage, turnips, carrots, pumpkins, watermelons, buckwheat, rye and oats. Around planting time, any of us who wanted to keep a garden would call for Auntie Bee to toss the seeds into the ground. There was a superstition going around that her touch was needed to make them grow. Nobody starved at our place.

Posted By: Richard Kigel

Posted By: Richard Kigel

Monday, May 17th 2010 at 9:43PM

You can also

click

here to view all posts by this author...